At Crossnore we approach all of our work (with clients, staff, and other stakeholders) with a trauma-informed lens. We have all experienced trauma. And we know that the experience of trauma affects our brains and bodies. We also know that we have all had positive experiences that buffer us from toxic stress. These buffers help us thrive in light of challenging events. People experience once type of trauma that is less frequently discussed: spiritual trauma or traumatizing theology.

Traumatizing Theology

Rev. Dr. Carol Harston, an ordained Baptist minister and pastoral researcher, defines traumatizing theology as “the image of God who threatens to shame, blame, or condemn. This image of God blends divine love with warnings of punishment to dissuade one from specific actions identified as wrong by the preacher, denominational leader, or parental figure.” Harston’s research shows us that the impact of theological trauma can have the same effects on a person as other kinds of trauma. Things like helplessness, anxiety, or loss of belonging. Traumatizing theology separates people from their religious or spiritual community. But it can also make them feel separated from the divine.

Traumatizing Theology and Entrance into Foster Care

Some children’s entrance into the child welfare system in the United States is connected with traumatizing theology. I have seen youth land in foster care because of becoming pregnant outside of marriage. And sometimes children who identify as a member of the LGBTQIA community find themselves unwelcome in their home of origin.

Some theologies shame, blame, or condemn these experiences. And because of this traumatizing theology, a child’s family stability erodes. For many children, their experience with faith and religion may be mixed. On one hand, they feel loved and supported by the community of faith. They remember some fun and meaningful experiences. But at the same time they feel shame for what has happened to them or how they identify. This can be very confusing to a child, youth, or young adult. Harston’s research on traumatizing theology highlights the importance of agency in establishing a trauma-resilient religious or spiritual community.

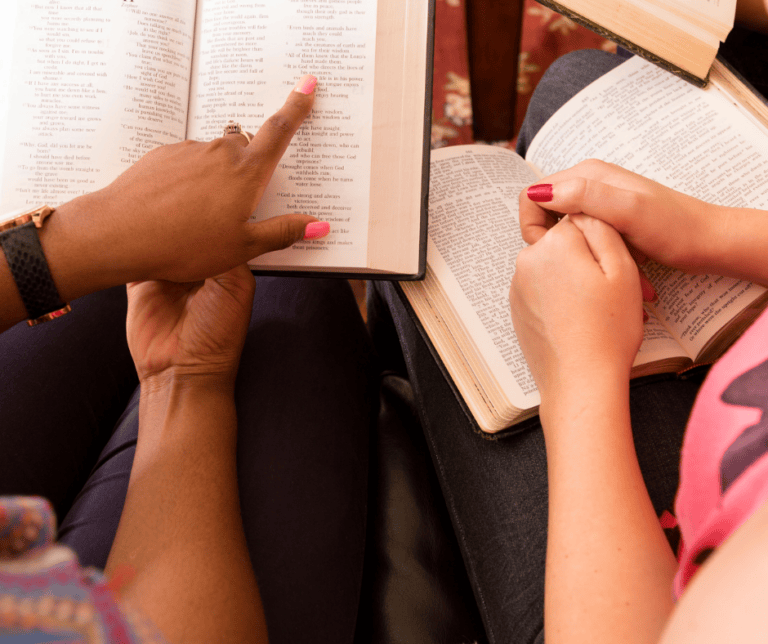

The Importance of Spiritual Communities and Traditions

Raising a child in a religious or spiritual community is a part of healthy parenting. Bringing a child to your faith community and exposing them to theology and ritual are important to their childhood. At each stage of child development, agency in a child’s religious or spiritual development looks different. For young children, play is a critical part of understanding our religious community. I recently saw a reel on social media of a child baptizing all his stuffed animals in the bathtub. What a beautiful and fun way to begin learning about his family’s religious tradition! Even though all those animals had to dry, I love that his parents allowed him to use play to explore this part of his life.

For elementary students, agency in religious or spiritual development may look like reading stories and teaching children creeds or rituals of a faith tradition. All the while maintaining safe spaces for healthy conversations when questions come up. For adolescents, agency may mean creating opportunities for youth to try different experiences of faith. And also understanding that it is age appropriate (and healthy!) to question and wrestle with religious concepts. At each stage (including into adulthood) religious and spiritual communities should be mindful of how they create opportunities for people to maintain safety through their own agency. This buffers them from experiences that cause them shame, blame, or condemnation.

At Crossnore we are mindful in our development of our spiritual life programs of embodying these concepts in all that we do. Religion and spirituality should be a protective and positive part of childhood, not something we weaponize or use to cause harm.