Before we dive in, let’s remember that being fearless is not a thing. As noted in the Fear episode on the Ologies podcast, celebrating someone for being fearless is like celebrating them for not feeling hunger–it’s just not possible!

We All Experience Fear

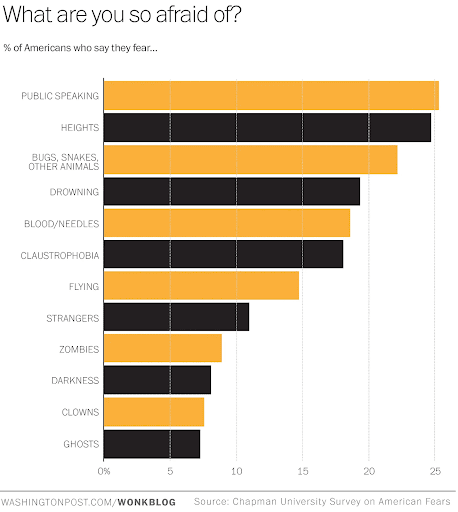

Growing up, my Scoutmaster regularly told us that the biggest fear in the US was public speaking. In fact, even renowned climber Alex Honnold–whose brain responds to fear differently when viewed on a brain scan–has a fear response to public speaking! As such, our leaders made available every opportunity for us to speak. They would give us feedback and encourage us to give feedback to our peers on how we did. As an adult, I can say that I still feel some gurgles and squiggles when I first get in front of a crowd. But when I get into my groove, I can feel pretty electrified by the process. I can attribute a lot of my current comfort to those formative experiences, and the learning community that our leaders built and helped us to sustain.

A Cultural View of Fear

In our day-to-day life, we all experience fear. It’s a core message from our nervous system, trying to keep our bodies and our beings safe. At work, our nervous systems may fire off those fear warnings. But, our organization and team culture can help to buffer those responses. As scholar and author Amy Edmondson points out, “a fearless workplace is one where employees feel that their opinions count.”

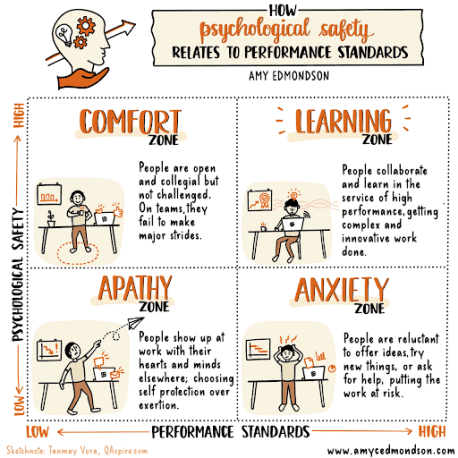

Edmondson is well-known for her research on Psychological Safety within teams, which has garnered huge support across the organization development world. Teams with high psychological safety are more engaged and motivated, better at decision making, more outspoken with opinions and concerns, more diverse with perspectives, and foster continuous learning environments. As we collectively face higher levels of stress, burnout, and turnover, this concept is critical to us supporting each other and the mission that drives our work.

Psychological Safety

Across our culture, you can find “motivational” posters or sayings that allude to fear being a feeble limitation to be conquered, rather than a tool or a gift from our nervous system. These quotes, such as, “If you aren’t living fearlessly, you aren’t living,” push us towards numbness and dissociation. In our culture, fear is equated with weakness, instead of the existence of humanity.

You can imagine the archetypal “bad boss.” You’ve seen them on movies and shows, and you may have even had one (or a few). They can be super motivational, encouraging you to reach outside your comfort zone, and push to reach your “highest potential.” Briefly, you may even feel superhuman. And yet, when something goes amiss, they weaponize your fear response. Through an unsafe work environment, unrealistic expectations, and positioning of power.

This is not to say that psychological safety means that teams are held to low standards. Psychological safety and high standards are not mutually exclusive! Much like what it takes to support resilience building in young people, leaders must communicate high standards. They have to create the container where missed marks and shortcomings turn into learning opportunities, instead of shame or manipulation. Again, how we exist together is more important than having the all-stars in the same room.

The “Magic” Within a Good Team

In 2012, Google completed Project Aristotle across 180 teams and 250 different team attributes, trying to figure out what’s the “magic” within the best teams. In this study, they could not find a clear pattern of characteristics to create an algorithm-inducing dream-team. Instead, they found that how the team works together is more important than who is on the team. The highest performing teams showed psychological safety, dependability, structure and clarity, meaning, and knew the impact of their work.

When we recognize that fear is a gift and a tool for us individually and collectively, we can embrace the gifts of psychological safety within our teams. One of the ways that Amy Edmondson prioritizes this learning is by asking the question, “What did you learn?”

What are the lessons you’re learning right now? Who is someone you could share this learning with? How might your learning help others succeed and validate their own experience?